Article

SQL join types

Learn everything you need to know about using different SQL join types.

This article looks at different types of SQL joins. If you’re new to the subject you may want to check out the SQL joins article as well. Please note that joins only work with relational databases.

Quick review of SQL Join Types

A SQL join tells the database to combine columns from different tables. We normally join tables by matching the foreign keys in one table to the primary keys in another. For example, every record in the products table has a unique ID in the products.id field: that’s the primary key. To match the key, every record in orders has a product ID in the orders.product_id field: that’s a foreign key. If we want to combine information about an order with information about the product that was ordered, we can do an inner join:

SELECT

orders.total as total,

products.title as title

FROM

orders INNER JOIN products

ON

orders.product_id = products.id

It’s very important that we use Orders.product_id and not Orders.id in the join: both fields are just numbers, so some order IDs will match some product IDs, but those matches will be meaningless.

The problem with SQL joins explained

Even if we use the correct fields, there is a trap here for the unwary. It’s easy to check that every record in Orders contains a product ID—a count of the number of null values in Orders.product_id returns 0:

SELECT

count(*)

FROM

orders

WHERE

orders.product_id IS NULL

| count(*) |

| -------- |

| 0 |

But what if things don’t always match? For example, suppose we’re trying to find out which products lack reviews. If we look at the reviews table, it has 1,112 entries:

SELECT

count(*)

FROM

reviews

| count(*) |

| -------- |

| 1112 |

Every single review refers to a product:

SELECT

count(*)

FROM

reviews

WHERE

reviews.product_id IS NULL

| count(*) |

| -------- |

| 0 |

But does every product have reviews? To find out, let’s count the number of products:

SELECT

count(*)

FROM

products

| count(*) |

| -------- |

| 200 |

We can then combine the products and reviews table and count the number of distinct products in the result. (In real life we’d probably use SELECT COUNT(DISTINCT product_id) FROM reviews to get this number, but using INNER JOIN helps us illustrate the idea.)

SELECT

count(distinct products.id)

FROM

products INNER JOIN reviews

ON

products.id = reviews.product_id

| count(*) |

| -------- |

| 176 |

Only 176 of the 200 products have any reviews. As a result, if we count the number of reviews for each product, we’ll only get the counts where there were some reviews—our query won’t tell us anything about products that lack reviews because the inner join won’t find any matching when combining the tables. This query demonstrates the problem:

SELECT

products.title as title, count(*) as number_of_reviews

FROM

products INNER JOIN reviews

ON

products.id = reviews.product_id

GROUP BY

products.id

ORDER BY

number_of_reviews ASC

| products.title | number_of_reviews |

| ------------------------- | ----------------- |

| Rustic Copper Hat | 1 |

| Incredible Concrete Watch | 1 |

| Practical Aluminum Coat | 1 |

| Awesome Aluminum Table | 1 |

| ... | ... |

We’ve ordered the result in ascending order by count; as this shows, the lowest count is 1, when it should be 0.

Outer SQL join types to the rescue

All right: we know how many products don’t have reviews, but which ones are they? One way to answer that question is to use the type of SQL join known the left outer join, also called a “left join”. This kind of join always returns at least one record from the first table we mention (i.e., the one on the left). To see how it works, imagine we have two little tables called paint and fabric. The paint table contains three rows:

| brand | color |

| --------- | ----- |

| Premiere | red |

| Premiere | blue |

| Special | blue |

while the fabric table contains just two rows:

| kind | shade |

| ------ | ----- |

| nylon | green |

| cotton | blue |

If we do an inner join on these two tables, matching paint.color to fabric.shade, only the blue records match:

SELECT

*

FROM

paint INNER JOIN fabric

ON

paint.color = fabric.shade

| paint.brand | paint.color | fabric.kind | fabric.shade |

| ----------- | ----------- | ----------- | ------------ |

| Premiere | blue | cotton | blue |

| Special | blue | cotton | blue |

Nothing in the fabric table is red, so the first record from paint isn’t included in the result. Similarly, nothing from paint is green, so the nylon material from fabric is discarded as well.

If we do a left outer join, though, the database keeps every record from the left table that lacks a match. Since there aren’t matching values from the right table, SQL fills in those columns with NULL:

SELECT

*

FROM

paint LEFT JOIN fabric

ON

paint.color = fabric.shade

| paint.brand | paint.color | fabric.kind | fabric.shade |

| ----------- | ----------- | ----------- | ------------ |

| Premiere | red | NULL | NULL |

| Premiere | blue | cotton | blue |

| Special | blue | cotton | blue |

Keeping all of the records from the left table turns out to be useful in a lot of different situations. For example, if we want to see which paints don’t have matching fabrics, we can do a left outer SQL join:

SELECT

*

FROM

paint LEFT OUTER JOIN fabric

ON

paint.color = fabric.shade

| paint.brand | paint.color | fabric.kind | fabric.shade |

| ------------ | ----------- | ------------ | ------------ |

| Premiere | red | NULL | NULL |

| Premiere | blue | cotton | blue |

| Special | blue | cotton | blue |

This is easier to read if we select only the rows where the values from the right-hand table are NULL:

SELECT

*

FROM

paint LEFT OUTER JOIN fabric

ON

paint.color = fabric.shade

WHERE

fabric.shade IS NULL

| paint.brand | paint.color | fabric.kind | fabric.shade |

| ------------ | ----------- | ------------ | ------------ |

| Premiere | red | NULL | NULL |

We can use this technique to get a list of products that don’t have any reviews by doing a left outer join and keeping only the rows where reviews.product_id has been filled in with NULL:

SELECT

products.title

FROM

products LEFT OUTER JOIN reviews

ON

products.id = reviews.product_id

WHERE

reviews.product_id IS NULL

| products.title |

| ----------------------- |

| Small Marble Shoes |

| Ergonomic Silk Coat |

| Synergistic Steel Chair |

| ... |

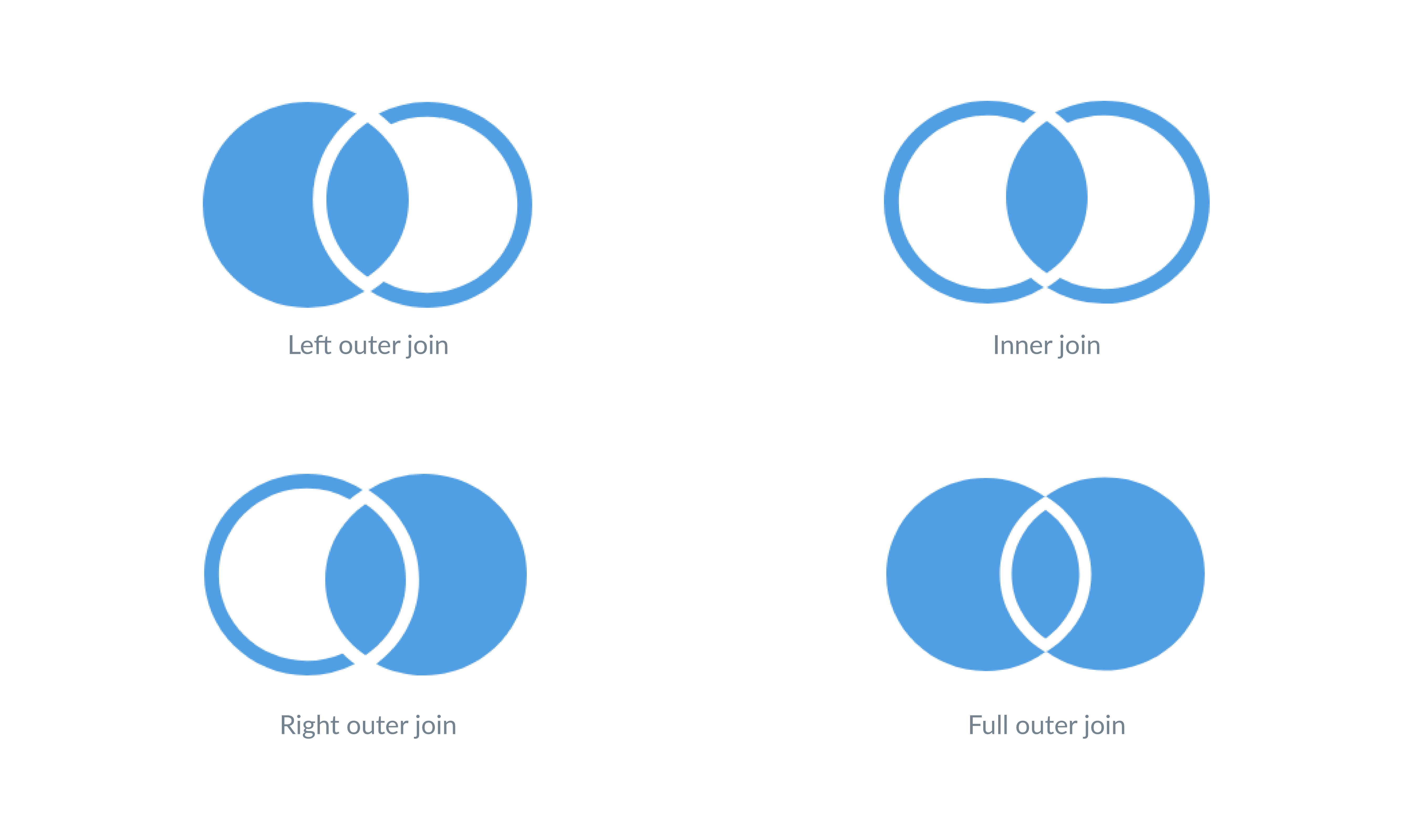

What about right outer SQL join and full outer join?

The SQL standard defines two other kinds of SQL join types for the outer join, but they are used much less often—so much less than some databases don’t even implement them. A right outer join works exactly like a left outer join, except it always keeps rows from the right table and fills columns from the left table with NULL when there aren’t matches. It’s pretty easy to see that you can always use a left outer join instead of a right one by swapping the tables around; there’s no particular reason to favor one over the other, but almost everyone uses the left-handed form, so we suggest you do too.

A full outer join keeps all of the information from both tables. If a record on the left lacks a match on the right, the database will fill in the missing right-hand values with NULL, and if a record on the right lacks a match on the left, it fills in the missing left-hand values. For example, if we do a full outer join on paints and fabrics we get:

| paint.brand | paint.color | fabric.kind | fabric.shade |

| ------------ | ----------- | ------------ | ------------ |

| Premiere | red | NULL | NULL |

| Premiere | blue | cotton | blue |

| NULL | NULL | nylon | green |

| Special | blue | cotton | blue |

Full outer joins are occasionally useful for finding the overlap between two tables, but in twenty years of writing SQL, I have only ever used them in lessons like this one.

Which SQL join type to use?

To review, there are four basic types of joins. Inner joins only keep records that match, and the other three types fill in missing values with NULL. Some people think of the left table as the main or initial table; the type of join you use will determine how many records from that initial table you’ll return, as well as any additional records you’ll return based on the columns you want from the other table. We’ve already seen exceptions to this here (there were multiple reviews for each product, for example), but that’s a good sign you have a good primary table to start with.

In general, you’ll only really need to use inner joins and left outer joins. Which join type you use depends on whether you want to include unmatched rows in your results:

- If you need unmatched rows in the primary table, use a left outer join.

- If you don’t need unmatched rows, use an inner join.

For another angle on joins that abstracts away the SQL, check out our article on joins using Metabase’s query builder.

Common problems with SQL joins

Doing an inner SQL join instead of an outer join

This is probably the most common error. Real data often has gaps, and inner joins will discard records without warning you whenever keys don’t line up. Counting the number of rows from one table that don’t have matches in another is a good safety check; if there are any, you should think about using an outer join instead of an inner one.

Using SQL joins on “matches” that aren’t meaningful

A person’s weight in kilograms and the value of their last purchase in dollars are both numbers, so it’s possible to do a join by matching them, but the result will (probably) be meaningless. A less frivolous example comes up when one table contains several foreign keys that refer to different tables, which can lead to joining patient data with vehicle registrations instead of appointment dates. Declaring foreign keys in tables can help prevent this.

Confusing NULLs in data with NULLs from mis-matches

If one of the tables in an outer join contains NULLs, we may wind up with a column with values that are missing because they weren’t in the original data and because of mismatches. Depending on the problem we’re trying to solve, these different “flavors” of NULL may matter.