‧

7 min read

Lessons learned from building AI analytics agents: build for chaos

Thomas Schmidt

‧ 7 min read

Share this article

Last year, I came back from a conference, pulled the latest code, and fired up our brand new version of Metabot to show our CEO the progress we’d made. While I was away, the team had been shipping new features and improvements.

My excitement quickly turned into one of the most embarrassing moments of my professional career. Metabot had transformed into a confused intern: eager to help but unable to remember what tools it had or how to use them.

But here’s the thing: this disaster taught us a lot about building production AI agents. In this post, I’ll walk you through what actually broke, why it happened, and the patterns we discovered that actually work in production for us.

If you want the full story with all the details, you can watch the talk we gave at the AI Engineering conference 2025 in Paris.

What we were building (and why it’s hard)

When we started building Metabot, the text-to-SQL space was already crowded: you describe what you want, give an LLM your database schema, and it generates SQL. Easy, right?

Yes and no.

The happy path works great - you’ve probably seen the demos with 5 well-documented tables and simple questions. But even if it works, there’s a problem: not everyone speaks SQL. A query can look fancy and return results, but how do you know if it’s answering the right question?

We wanted to go beyond SQL generation. Our goal was to leverage the Metabase query builder, a visual interface where users can click together queries and actually see what filters and aggregations are applied. This gives non-SQL users a way to validate and iterate on results themselves more easily.

But here’s where it gets hard:

- SQL is baked into LLM training data. Our query builder language? Not so much.

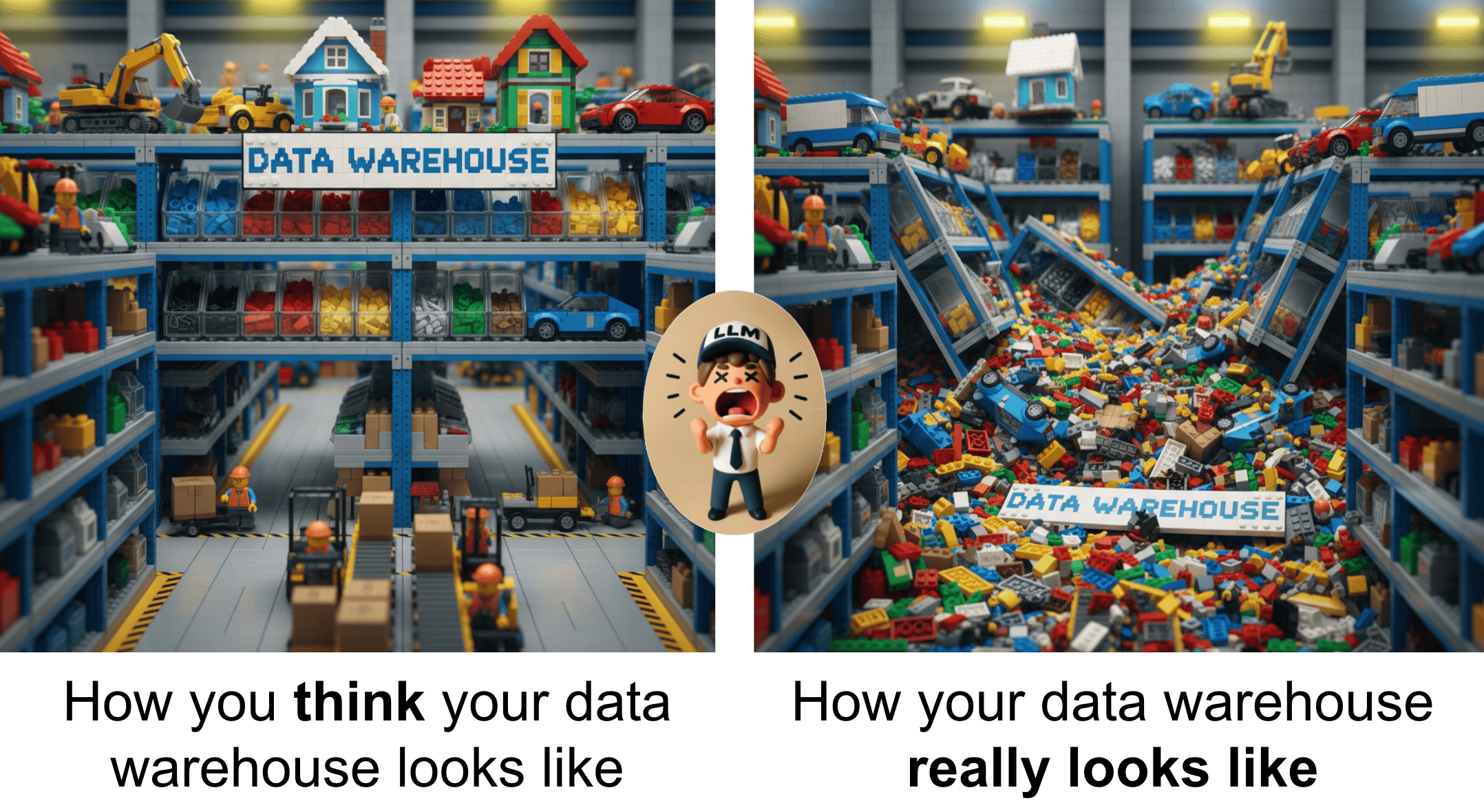

- Real customer data is messy: hundreds of tables, vague descriptions, legacy cruft.

- Humans are notoriously bad at providing context: “How many customers did we lose?” (Which time period? What’s a “customer”? Logo churn or revenue churn?)

The real challenge wasn’t query generation. It was building an agent that could navigate this chaos by understanding what users are looking at, what they actually mean, and helping them find answers even when they don’t know how to ask the question.

That’s what Metabot set out to do. And that’s what spectacularly broke.

What broke: local optimization

The demo failure traced back to parallel development without integration testing. One engineer perfected the context awareness to make sure Metabot knew exactly what dashboard you were looking at. Another engineer optimized the querying tool, fine-tuning descriptions, parameters, and prompts until it worked beautifully in isolation.

Together, they created chaos.

The LLM doesn’t experience your architecture. It sees one context window: every instruction, every tool description, every piece of dynamic state, flattened into a single prompt. Our individually-optimized components were sending contradictory signals. Tool descriptions assumed different conventions. Instructions overlapped and conflicted. The model couldn’t figure out what we wanted because we were telling it multiple inconsistent things simultaneously.

The fix required thinking differently about what we were building. We weren’t building a querying tool with some context features. We were building a context engineering system. The LLM handles the generation; our job is to ensure it sees clean, unambiguous context at every decision point.

What worked: context engineering over prompt engineering

We stopped front-loading prompts and started engineering context throughout the agent’s lifecycle. Three patterns—optimized data representations, just-in-time instructions, and actionable error guidance—transformed how the LLM understood and used its tools

LLM-optimized data representations

We stopped dumping raw API responses into the context. Instead, we built explicit serialization templates for every data object Metabot works with — tables, fields, dashboards, questions — optimized for LLM consumption:

<table

id=""

name=""

database_id=""

>

### Description ### Fields | Field Name | Field ID |

Type | Description | |------------|----------|------|-------------|

</table>

This structured format gives the LLM consistent, hierarchical context it can parse reliably. Table metadata, field types, and relationships are always in the same place, reducing hallucination and tool misuse. The format is also reusable across all of Metabot’s tools, so when one person optimizes it, everyone benefits.

Use this pattern when your agent works with complex domain objects that appear across multiple tools or conversation turns.

Just-in-time instructions

Our original architecture front-loaded everything into the system prompt. The LLM ignored most of it.

So we tried something different: include instructions in tool results, right in the relevant moment:

{

"data": "Chart created with ID 123",

"instructions": """Chart created but not yet visible to the user.

To show them:

- Navigate: use navigate_to tool with chart_id 123

- Reference: include [View chart](metabase://chart/123) in your response

"""

}

When a chart gets created, tell the LLM right then how to show it. The LLM pays attention to context that shows up exactly when it’s relevant, not buried in a system prompt from 20 messages ago.

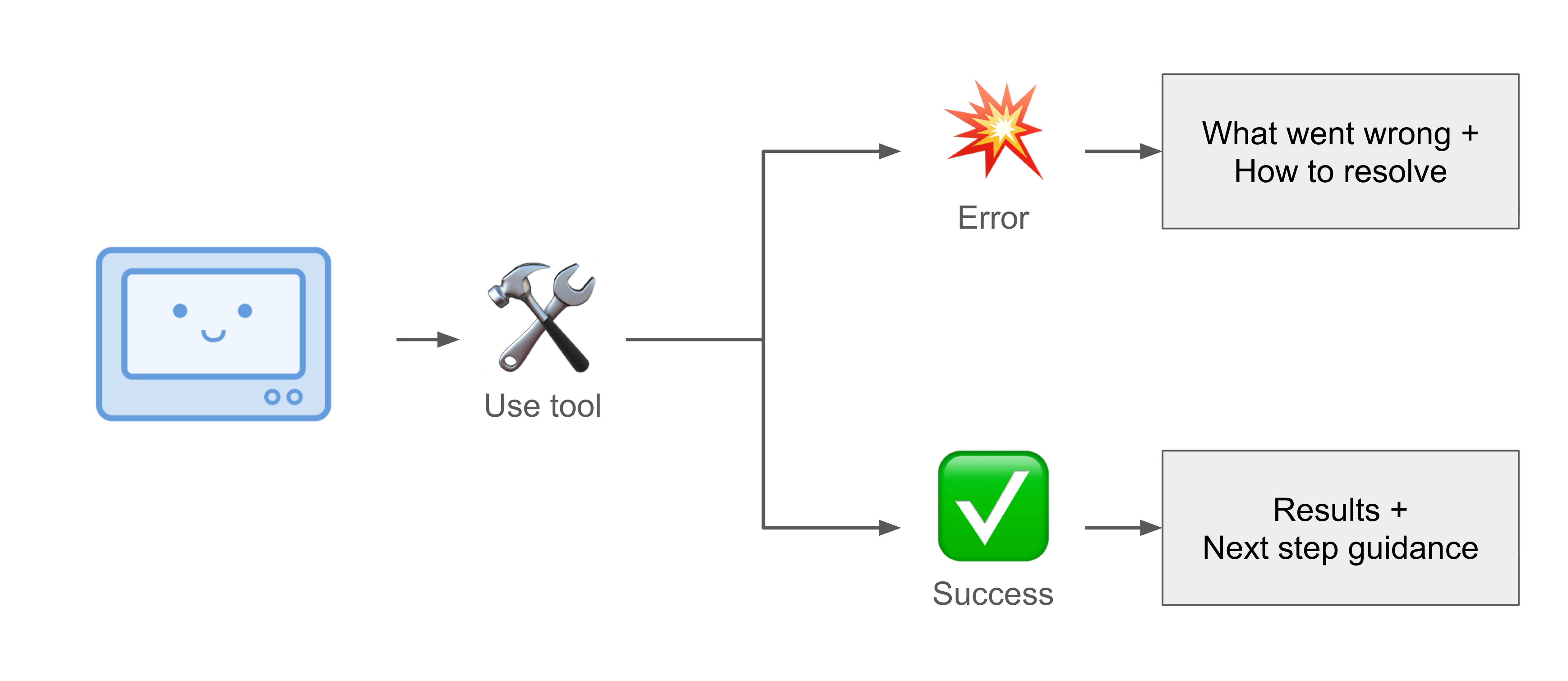

Explicit error guidance

This pattern is more commonly known, but worth emphasizing: don’t just return error messages, return recovery paths instead.

{

"error": "Table 'orders_v2' not found",

"guidance": """This table may have been renamed or deprecated.

Try:

1. Search for tables matching 'orders'

2. Check if 'orders' or 'order_items' fits your query

3. Ask the user which orders table they want to use"""

}

The LLM handles ambiguity much better when you tell it how to handle ambiguity.

The benchmark problem in AI analytics agents

After the demo disaster, we built benchmarks. Scores climbed into the 90s, but perceived quality dropped.

The issue is subtle but important: engineers write benchmark prompts like engineers. “Count of orders grouped by created_at week.” Clean, precise, all context provided.

Real people say: “Why is revenue down?”

That question is missing a time period, revenue definition, comparison baseline, and probably some context about what triggered the question in the first place. And even if you nail the realistic test cases, there’s the uncontrollable data mess underneath - legacy tables, missing descriptions, inconsistent naming. The gap between benchmark coverage and production chaos is where AI products fail.

We now treat benchmarks as integration tests, not pure quality measures. If a change drops the score, something broke. But a passing score doesn’t mean the agent works, just that it handles clean inputs correctly. The real evaluation is production feedback, analyzed through a lens of what people actually asked versus what they needed.

Build for chaos, not happy paths

Our initial Metabot hackathon prototype had 5 perfectly documented tables and worked beautifully. Production has hundreds of tables with varying quality, used by people who phrase questions in wildly creative ways, and with edge cases we never imagined.

That’s the core lesson: don’t build for the happy path. Every polished demo with clean data creates expectations you can’t meet. People wander off the happy path in seconds. Better to understand the chaos, build for it, and deliver consistently than to show something impressive that falls apart on contact with reality.

We learned this the hard way. But it forced us to focus on what actually matters: robust context engineering, handling messy data gracefully, and building for the chaos that production inevitably brings.

Try it yourself

Metabot is now out of beta in Metabase. You can try it with your own data and see how these patterns work in practice. Pro tip: Do your homework and set up your semantic types like foreign key relations, metrics and segments. This will help improve the experience.

Want the full technical deep dive? Watch the complete talk from AI Engineer Paris 2025 where we go deeper into the implementation details.

These patterns apply beyond analytics agents. Any time you’re building with LLMs, think about the full context window, deliver instructions when they’re actionable, and always (always!) build for the chaos.